Presidential Campaign and the Carter Presidency

When he embarked on his quest for the presidency in 1974, he was a politician so little known that political pundits greeted his candidacy with the question, “Jimmy who?” His successful 1976 presidential campaign strategy was based on renewing the nation’s spirit and reforming its government following the national doldrums and divisions of the post-Watergate, post-Vietnam era.

In that campaign, Jimmy Carter promised to strive for “a government as good as its people,” an administration that would not be “business as usual” or “go along to get along.” When he emerged victorious over President Gerald R. Ford, President Carter made good on those pledges, sometimes to the consternation of the political establishment, including leaders of his own party.

The Carter Presidency

Jimmy Carter was sworn in as president of the United States on January 20, 1977, by Supreme Court Chief Justice Warren Burger. (Credit: Jimmy Carter Presidential Library)

Jimmy Carter was sworn into office on January 20, 1977. On a day full of promise, he surprised the nation by walking down Pennsylvania Avenue along the inaugural parade route from the U.S. Capitol to the White House. In Keeping Faith: Memoirs of a President, he wrote of the reaction as he and Mrs. Carter emerged from the presidential limousine: “There were gasps of astonishment and cries of ‘They’re walking! They’re walking!’ The excitement flooded over us; we responded to the people with broad smiles and proud steps. It was bitterly cold, but we felt warm inside ... We were surprised at the depth of feeling from our friends along the way. Some of them wept openly, and when I saw this, a few tears of joy ran down my cold cheeks. It was one of the few perfect moments in life when everything seems absolutely right.”

President Carter’s most praised successes in office were the Camp David Accords and the subsequent peace treaty between Egypt and Israel; the Panama Canal treaties; the establishment of full diplomatic relations with China; and the advancement of human rights, making this a continuing principle of American foreign policy. Determined to increase diversity, he appointed more women, African Americans, and Hispanics to judgeships and senior positions than all of his 38 predecessors combined. He won passage of the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act, the largest conservation action ever, which more than doubled the size of the U.S. National Park and Wildlife Refuge System and tripled the size of the U.S. Wilderness System. And, as the first president from the Deep South since before the Civil War, he helped to heal the wounds of racial discrimination and division.

A number of other battles and accomplishments have taken on added significance as history has underscored their importance: his campaign for a national energy policy; a politically costly struggle with inflation, which had escalated dramatically because of the oil shock of 1979-80, when worldwide oil prices doubled; a vigorous campaign against nuclear proliferation; an effort to provide health insurance for children and families; and a major focus on education, including the creation of the Department of Education and dramatically increased funding for early childhood education as well as college tuition assistance. Further, President Carter pushed through much-needed deregulation of airlines, rail, and trucking, and the loosening of government controls over financial services and communications—actions that made the American economy more flexible and efficient and better prepared for the global competition of the 21st century.

President Carter was defeated in his re-election bid in large measure because of issues he had devoted much time and effort to resolving: the Iran hostage crisis; the state of the U.S. economy, including the adverse effects of American dependence on imported oil; the Soviet Union’s continued intervention in Afghanistan; and ideological divisions within his own party.

Human Rights

In his January 14, 1981, farewell message to the nation, President Carter said: “Our American values are not luxuries, but necessities—not the salt in our bread but the bread itself. Our common vision of a free and just society is our greatest source of cohesion at home and strength abroad, greater even than the bounty of our material blessings.”

As president, his espousal of human rights had been criticized by much of the foreign policy establishment and many foreign leaders as being naïve and counterproductive. But it had two major long-term impacts. In Latin America, the change in the 1980s from military dictatorships to democracies, which still holds today, was strongly influenced by the firm stand President Carter took against repressive policies in Argentina, Chile, and elsewhere. His support for the right of dissidents to speak out in the Soviet Union, from Anatoly (Natan) Scharansky to Andrei Sakharov, and for the protection of the Polish Solidarity Movement from Soviet intervention, were essential influences on the unraveling of the Soviet communist system.

President Carter wrote in Keeping Faith, “I was often criticized, here and abroad, for aggravating other government leaders and straining international relations. At the same time, I was never criticized by the people who were imprisoned or tortured or otherwise deprived of basic rights. When they were able to make a public statement or to smuggle out a private message, they sent compliments and encouragement, pointing out repeatedly that the worst thing for them was to be ignored or forgotten. This was particularly true of prisoners behind the Iron Curtain.”

Legislative Record

President Carter’s relationship with Congress was frequently rocky because of his disinclination to defer controversial issues and refusal to accept "half a loaf" while he thought more was possible. Despite the controversy, his legislative record of success was impressive, 76.4 percent, according to Congressional Quarterly, placing him third-highest among post-WWII presidents (Johnson, 84.4; Kennedy, 83.0). In Keeping Faith, he would acknowledge that his “relationship with Congress would have been smoother” and the “impression of undue haste and confusion would have been avoided” if he had attempted less. But, he maintained, “We would not have accomplished any more, and perhaps less.”

Energy Policy

The most notable example of his determination to tackle tough issues despite the political consequences was his four-year struggle to institute a national energy policy that would reverse America's growing dependence on imported petroleum and move the country toward alternative sources of energy. In an April 18, 1977, address to the nation, he predicted the difficulty of the task:

“Our decision about energy will test the character of the American people and the ability of the president and the Congress to govern this nation. This difficult effort will be the ‘moral equivalent of war,’ except that we will be uniting our efforts to build and not to destroy.”

In the process, he faced resistance within Congress and from various interest groups on the right and the left. He believed there needed to be incentives for both the development of energy resources and for conservation. Despite controversy and resistance, in the end, with the invaluable support of courageous congressional leaders from both parties, he gained enactment of 60 percent of his energy proposals. The United States was able to slash its dependence on foreign oil, cutting oil imports in half from 1977 to 1982, in significant part because of President Carter’s efforts.

He created the Department of Energy and deregulated oil and natural gas prices, allowing market forces to work and create incentives for traditional production. At the same time, he emphasized the importance of encouraging alternative sources such as solar, geothermal, and wind. He supported the use and development of ethanol and synthetic fuels. Instituting stiff standards for automobile fuel efficiency and incentives for home insulation saved energy that otherwise would have been wasted.

Some of President Carter’s more significant accomplishments were later reversed by his successors. His emphasis on massive energy research and development, fuel efficiency, and conservation lost support, and America slowly returned to an increasing dependence on imported oil.

President Carter endorsed the use of solar power as part of a comprehensive plan to strengthen the nation’s energy security. (Credit: Jimmy Carter Presidential Library)

In 1979, President Carter launched an ambitious plan to research and promote the use of solar energy. He had solar panels installed on the White House roof to provide both hot water and a high-profile symbolic example. While the panels remained until 1986, when they were removed for roof repairs and quietly not returned, funding for the solar energy program was gutted within months of President Carter leaving office. It was not until 2014 that solar panels were installed again on the roof of the White House.

President Carter failed to persuade Congress to enact higher taxes on gasoline or to create an energy mobilization board to speed the development of major energy projects. The Three Mile Island accident in 1978 made it politically impossible to win support for expanding the nuclear power industry. But even his failures emphasized the overarching importance he attached to the issue of energy security.

As he noted in his memoirs, “Our administration left the country with petroleum inventories at record levels, a natural gas surplus and a fair distribution system for it, more exploration under way for new petroleum than at any time in history, and an orderly plan for eliminating the unnecessary federal restraints. The rate of growth of domestic coal production doubled, and oil imports and even total consumption dropped rapidly. A substantial portion of the succeeding oil glut was caused by the worldwide shift to more efficient uses of energy and emphasis on fuels other than oil and gas.”

Had his energy policies been fully implemented and carried on in subsequent administrations, the U.S. and the world would be far better positioned to address climate change.

Middle East Peace Process

Egypt President Anwar Sadat, President Carter, and Israel Prime Minister Menachem Begin shake hands at the March 26, 1979, White House signing of the Israel-Egypt peace treaty that began an era of lasting peace between the two nations. (Credit: Jimmy Carter Presidential Library)

When President Carter left office, there was a wide consensus that his greatest accomplishment was the accord between Israel and Egypt, reached in 1978 at Camp David, the presidential hideaway in Maryland’s Catoctin Mountain Park. His intensive personal involvement in the negotiations, followed by an unprecedented round of presidential shuttle diplomacy in the Middle East to implement the agreements, produced a treaty of peace between Israel and its most powerful Arab neighbor that has continued to be honored by both countries, and a framework for resolving the Israeli-Palestinian issues that he believed would have been just as successful if it had been aggressively pursued by following administrations.

He was the first president to state unambiguously that the Palestinian people must have a “homeland” if there were to be a comprehensive peace agreement that would ensure Israel’s security. That statement provoked fierce criticism at the time. It foreshadowed other statements and actions by him in the decades that followed, all designed to move the peace process forward by pushing participants to deal with the facts.

In his memoirs, President Carter wrote, “Looking back on the four years of my Presidency, I realize that I spent more of my time working for possible solutions to the riddle of Middle East peace than on any other international problem. At the beginning, I never dreamed of the many hours of exhilaration and despair that lay ahead. As was the case with the Panama Canal treaties, I have asked myself many times if it was worth the tremendous investment of my time and energy. Here again, the answer has not always been the same. It will depend on the wisdom and dedication of the leaders of the future.”

Perhaps because even his successful efforts proved to be a political liability, and because of the difficulty of the issues, no succeeding president has pursued the peace process with anything approaching the same level of aggressive, personal commitment.

Africa Policy

Believing that Africa deserved far more attention from the United States, Jimmy Carter, in April 1978, became the first American president to pay a state visit to sub-Saharan Africa. The economy and culture of the United States had benefitted greatly from its African Diaspora, which had originated with Africans initially brought to American shores by the terrible Atlantic slave trade. He thought this created a special obligation to assist African nations in their efforts to achieve human rights and economic development. Optimistic about the potential of the people of Africa, he sought their partnership. President Carter worked to bring justice and majority rule to southern Africa, and his administration paid special attention to the people of that region, supporting those who were struggling to overcome apartheid and other forms of racism.

Panama Canal Treaties

President Jimmy Carter and Panamanian Gen. Omar Torrijos join other dignitaries at the signing ceremony for the Panama Canal treaties, June 16, 1978, in Panama City. (Credit: Jimmy Carter Presidential Library)

The Panama Canal treaties were strongly opposed by many conservatives, but received courageous support from Senate Minority Leader Howard Baker, former President Ford, Sen. Barry Goldwater, a number of other Republican senators, and some of the most conservative Southern Democrats. Less than two years later, although the most vocal critics of the treaties won control of both the legislative and executive branches, they made no effort to revoke, renegotiate, or reinterpret any significant aspect of the agreements.

President Carter’s determination to seek approval of the Panama Canal treaties was typical of the sort of issue his advisors frequently counseled him to defer to a second term, when there would no longer be re-election considerations. “And, what if there’s not a second term?” he responded more than once, making it clear that he was determined to move forward on issues he considered important to the nation, regardless of the political cost. In a highly personal campaign addressed to both the American people and Congress, he changed overwhelming opposition to the treaties into positive approval. The treaties were not only critical in preserving a peaceful relationship with Panama and assuring that the canal would remain free from terrorist incidents, but also added immeasurably to U.S. prestige throughout Latin America.

Defense and the Cold War

President Carter obtained the first real increase in defense spending since the Vietnam War, encountering opposition from the left, but also cancelled weapons systems that he considered to be an inefficient use of resources, drawing criticism from the right. He increased funding for stealth technology, cruise missiles, and special operations capabilities—decisions that history has clearly validated. He managed to obtain agreement from our NATO allies to an annual 3 percent real increase in defense spending. His introduction of theater nuclear weapons to Europe sent a strong message to the Soviet Union at a time when it was deploying new SS-20 missiles aimed at Europe. His determined response to the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan—economic sanctions, including a politically explosive embargo on grain sales; boycott of the 1980 Moscow Olympics; and the arming of the Afghan resistance—eventually helped lead the way to a Soviet withdrawal.

Given his strong identification with human rights and as a man of peace, many Americans came to view President Carter as a pacifist, a serious misreading of his record. Of 20th century presidents, only Dwight D. Eisenhower had a longer period of military service than did Jimmy Carter; and while instinctively opposed to the “unnecessary” use of military force, President Carter was fiercely proud that the strong defense policies of his administration helped set the stage for the end of the Cold War.

Robert M. Gates, CIA director under President George H. W. Bush and secretary of defense under both President George W. Bush and President Barack Obama, would write in his 1996 book, From the Shadows: The Ultimate Insider’s Story of Five Presidents and How They Won the Cold War: “I believe historians and political observers alike have failed to appreciate the importance of Jimmy Carter’s contributions to the collapse of the Soviet Union and the end of the Cold War. He was the first president during the Cold War to challenge, publicly and consistently, the legitimacy of Soviet rule at home. Carter’s human rights policy, . . . by the testimony of countless Soviet and East European dissidents and future democratic leaders, challenged the moral authority of the Soviet government and gave American sanction and support to those resisting that government.”

SALT and Nuclear Arms Reductions

At the conclusion of a summit meeting in Vienna, Austria, on June 18, 1979, U.S. President Jimmy Carter and Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev sign the SALT II treaty specifying guidelines and limitations for nuclear weapons. (Credit: Jimmy Carter Presidential Library)

Many of the same conservative critics who assailed the Panama Canal treaties also attacked President Carter’s aggressive proposal for “deep cuts” in U.S. and Soviet nuclear arsenals and the Strategic Arms Limitation Treaty he negotiated with the Soviet Union in 1979. Although the subsequent Soviet invasion of Afghanistan made ratification of SALT II politically impossible, both sides continued to honor provisions throughout the Cold War; and his once-reviled “deep cut” proposals became the basis for arms control agreements under both Presidents Ronald Reagan and George H. W. Bush.

'We Kept Our Country at Peace'

In a 2011 interview with The (London) Observer, President Carter summed up his perspective on much of his administration’s foreign policy activity this way: “We kept our country at peace. We never went to war. We never dropped a bomb. We never fired a bullet. But still we achieved our international goals. We brought peace to other people, including Egypt and Israel. We normalized relations with China, which had been nonexistent for 30-something years. We brought peace between the U.S. and most of the countries in Latin America because of the Panama Canal treaties. We formed a working relationship with the Soviet Union.”

The Modern Vice Presidency

Before 1977, American vice presidents primarily carried out ceremonial roles, often leading to frustration on their part; no vice president had played a sustained, substantive role in the executive branch. Jimmy Carter and Walter Mondale changed that for their administration and those that followed.

When, as a finalist for running mate, Mondale met with candidate Carter, there was an instant chemistry; the two men discovered they were both personally and politically compatible. Carter made it clear he wanted a partner who could help him accomplish the goals of his administration, and Mondale made it clear he wanted to be an integral part of policymaking as well as its implementation.

President Jimmy Carter and Vice President Walter Mondale in the Rose Garden on December 4, 1979. (Credit: Jimmy Carter Presidential Library)

Once elected, the two worked together closely, and for the first time in American history a president-elect involved his vice president-elect in Cabinet selection and policy development. President-elect Carter asked Mondale for a memorandum outlining his proposals for the office of the vice president. Mondale and his top aides studied the office and prepared a lengthy memo outlining his prospective role: He would have access to all information in the White House, including all intelligence reports; there would be regular meetings between the two; he would play a troubleshooting role as the president’s emissary to Congress, in foreign policy and in working out disputes with Cabinet and other officials; and he would serve as the president’s liaison to important political constituencies such as labor and the Democratic National Committee.

President Carter agreed to Mondale's requests. He also provided him an office in the West Wing and instituted a weekly private luncheon with him. These actions both symbolically and logistically made the vice president a far more important player in the executive branch. The president also integrated the vice president’s staff into his own senior staff and made it clear that any request from the vice president should be viewed by his staff and Cabinet as having come from the president himself. For all vice presidents who have followed Mondale, weekly luncheons with the president, a West Wing office, and a substantive role have been part of the position.

Health Insurance

In 1979, President Carter crafted and proposed a plan to provide basic health insurance for every American child and catastrophic coverage for every American family. With Democratic majorities in both houses of Congress and the prospect of significant Republican support, it should have passed easily; but key Democratic congressional leaders withheld support, with the stated hope of getting a more comprehensive bill later. Politics related to the upcoming battle for the 1980 Democratic presidential nomination were also a significant factor.

Inflation

In 1979, President Carter appointed Paul Volcker as chairman of the Federal Reserve, a bold move that served the national interest despite political costs to the administration. The United States and the rest of the industrialized world were in the tenth year of persistent, debilitating inflation, further exacerbated by the international oil shock of 1978-79. Volcker had briefed the President on the stringent policy he would impose if appointed. Having learned that less draconian measures did not work, President Carter gave him the job, knowing the politically poisonous monetary medicine that Volcker would administer. The political cost was huge: Short-term interest rates rose to 20 percent and unemployment spiked in the election year of 1980. But the medicine worked, though not in time to bring any political benefits to President Carter.

A Sea Change in Executive Branch and Judicial Appointments

In an unprecedented and successful effort to dramatically increase diversity, President Carter appointed more women, African Americans, and Hispanics to judgeships and senior positions than all of his 38 predecessors combined.

He doubled the number of women to ever hold a Cabinet post when he appointed three women to his Cabinet, one of whom was African American, and named two African Americans to the Cabinet-level position of U.S. ambassador to the United Nations.

By early 1980, women held 22 percent of President Carter’s 2,110 appointments. These included three of the five women to ever serve as under secretaries of a Cabinet department, 80 percent of all women to ever serve as assistant secretaries of a Cabinet department, and 40 percent of all women to ever hold an ambassadorial post.

When President Carter took office, no women had ever been appointed to the Federal Reserve Board, the Securities and Exchange Commission, or the Federal Home Loan Bank Board. He named a woman to each of them. No women had ever been general counsel of a Cabinet department. He appointed six to those posts.

President Carter appointed 57 minority judges and 41 female judges to the federal judiciary, more than all previous presidents combined. Pre-Carter, only 31 minorities had ever been named to federal judgeships. He named 57. Pre-Carter, only eight women had ever been named to federal judgeships. He named 41. When President Carter left office, he had appointed 41 of the 46 women serving as federal judges.

Although there were no vacancies on the Supreme Court during his term, President Carter appointed two judges to the U.S. Court of Appeals who were later elevated to the Supreme Court: Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Stephen Breyer.

Iran Hostage Crisis and 1980 Presidential Election

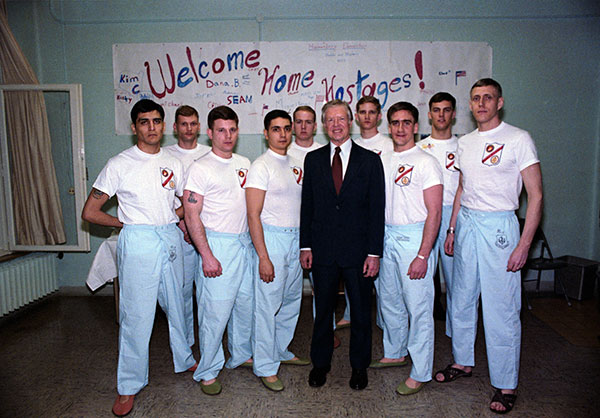

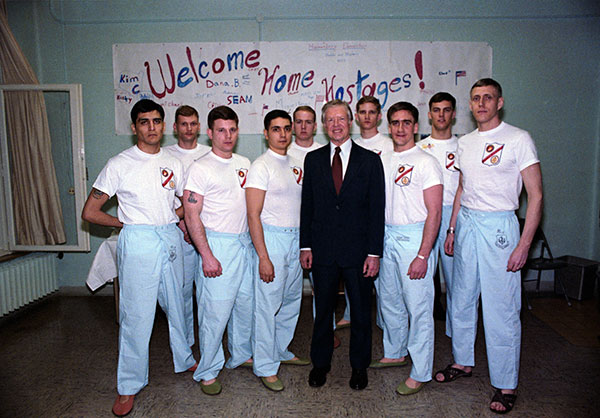

Former President Jimmy Carter meets with nine of the 52 freed American hostages in Wiesbaden, West Germany, January 22, 1981. (Credit: Jimmy Carter Presidential Library)

The persistence, physical energy, and attention to crucial details that were hallmarks of President Carter's approach to the presidency also were applied in responding to the seizure of American hostages in Iran. All the hostages were eventually freed without a confrontation that could have provided the Soviet Union with a significant strategic opening in a vital and unstable region, but public frustration over the lengthy captivity and an unsuccessful rescue attempt contributed substantially to his failure to win re-election.

Despite the continuing hostage crisis, the nation’s economic woes, and continuing division within the Democratic Party, the presidential race between President Carter and Gov. Ronald Reagan was close as the campaign entered its last weekend. Two days before the election, a new message from the Iranian government made the release of the hostages seem possible. President Carter canceled campaign appearances and flew back to Washington. In Keeping Faith, he recalled, “Now my political future might well be determined by irrational people on the other side of the world over whom I had no control. If the hostages were released, I was convinced my reelection would be assured; if the expectations of the American people were dashed again, there was little chance that I could win.”

On the day before the election, it became clear the hostages would not be released in the near future. That day also happened to be the first anniversary of the taking of the hostages. Yet again, news coverage was dominated by grim reminders of another disappointing delay, the failed rescue operation, and Americans still held hostage. What President Carter described in his memoirs as a "wave of disillusionment" swept the country, leading to "a precipitous drop in support" and an overwhelming victory for Reagan.

On January 20, 1981—at the very moment President Carter was watching Reagan sworn in as his successor—the hostages were finally released. They had been held for 444 days.

Of that day, President Carter wrote in Keeping Faith: "It is impossible for me to put into words how much the hostages had come to mean to me, or how moved I was that morning to know they were coming home. At the same time, I was leaving the home I’d known for four years, too soon for all I had hoped to accomplish. I was overwhelmed with happiness—but because of the hostages’ freedom, not mine."