Citizen Carter: The Post-Presidency

The Carter Center

In his “Farewell Address to the Nation” in January 1981, President Carter said, “In a few days I will lay down my official responsibilities in office to take up once more the only title in our democracy superior to that of president, the title of citizen.”

And he meant that. After a brief period of decompression, President and Mrs. Carter went back to work to serve the ideals that had guided their lives. In 1982, President Carter became University Distinguished Professor at Emory University in Atlanta and, in partnership with Emory, he and Mrs. Carter founded The Carter Center to “wage peace, fight disease, and build hope” in nations around the world.

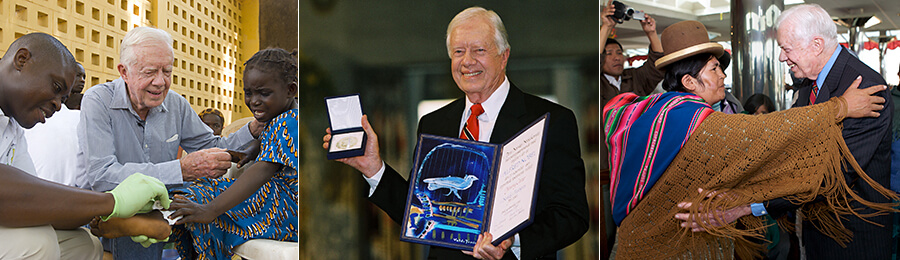

Since its founding, the nonpartisan, not-for-profit Center has had numerous achievements: leading the international campaign to eradicate Guinea worm disease, which has reduced cases by more than 99.99 percent; helping establish grassroots health care delivery systems in thousands of communities in Africa; observing more than 110 elections in 40 countries; furthering avenues to peace in Ethiopia, Eritrea, Liberia, Sudan, Uganda, the Korean Peninsula, Haiti, and Bosnia and Herzegovina; expanding efforts to diminish stigma against people with mental illness; and strengthening international standards for human rights.

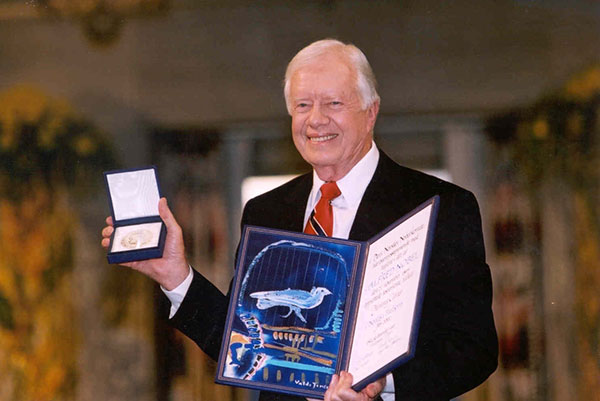

In 2002, during the 20th anniversary year of the Carter Center’s founding, President Carter was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize “for his decades of untiring effort to find peaceful solutions to international conflicts, to advance democracy and human rights, and to promote economic and social development.”

The Center’s headquarters are located at the Carter Presidential Center complex in Atlanta, which was dedicated in October 1986 and also includes the Jimmy Carter Presidential Library and Museum, administered by the National Archives. President Carter celebrated his 85th birthday on October 1, 2009, with the reopening of a totally redesigned Jimmy Carter Presidential Museum. It is the first presidential museum to highlight a president’s post-presidential career, a period that for President Carter was substantially longer than his political career. The Jimmy Carter National Historic Site in Plains, Georgia, which includes President Carter’s boyhood home, is administered by the National Park Service.

Health

Jimmy Carter consoles a young Guinea worm patient in Savelugu, Ghana, in February 2007. The Carter Center leads the international campaign to eradicate Guinea worm disease. (Credit: The Carter Center)

Through its health programs, the Center has advanced disease prevention and agriculture in the developing world. Its campaign to eradicate Guinea worm disease was launched in 1986 when the disease afflicted an estimated 3.5 million people. By 2022, the Center and its partners had reduced the number of cases to 13. The Center also works on regional control and elimination of diseases such as river blindness (onchocerciasis), which affects nearly 18 million people in the Americas and Africa. River blindness is preventable through annual treatment with the medicine Mectizan®, donated by Merck. The Center has distributed more than 455 million treatments of Mectizan worldwide since the River Blindness Elimination Program began in 1996. In the Americas, the Center is working with ministries of health in affected endemic countries to halt transmission of the disease.

The Carter Center also targets four other tropical diseases: trachoma, malaria, lymphatic filariasis, and schistosomiasis. In the United States, as well as abroad, the Center strives to reduce the stigma of mental illness and improve access to and the quality of mental health care.

Peace

Activities of the Center often found the former president involved in unofficial diplomatic missions and conflict mediations that pursued new avenues to peace or eased tensions in such areas as Ethiopia and Eritrea (1989), Liberia (1991), North Korea (1994), Haiti (1994), Bosnia (1994), Sudan (1995), the Great Lakes region of Africa (1995-96), Sudan and Uganda (1999), Cuba (2002), Venezuela (2002-2004), and the Middle East (2008).

North Korea

North Korea President Kim Il-Sung welcomes Jimmy Carter to Pyongyang in June 1994 for talks that resulted in an eight-year freeze of North Korea's nuclear weapons program. (Credit: The Carter Center)

In 1994, President and Mrs. Carter received permission from President Bill Clinton to travel to North Korea to try to dissuade the North from pursuing a nuclear weapons program. The day before the Carters arrived in Pyongyang, the North Korean government withdrew its membership from the watchdog International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) and threatened to expel IAEA inspectors. The United States began pushing for U.N. sanctions against the North. With no means of direct communication, some began to fear the two countries were heading toward war.

After two days of talks, President Carter broke the nuclear impasse when President Kim agreed to freeze his country’s nuclear program in exchange for the resumption of his dialogue with the United States. As a gesture of good will, he also promised to allow joint U.S.-North Korean teams to search for and recover the remains of American soldiers killed in the Korean War.

The talks between the U.S. government and Pyongyang continued after President Carter’s visit and culminated in the signing of a U.S.-Korea agreement. International inspectors again began monitoring the North’s nuclear program.

In August 2010, President Carter returned to North Korea to seek the release of an American sentenced to eight years of hard labor for illegally crossing into that country from China. The humanitarian mission was a success, and the former president accompanied 30-year-old English teacher Aijalon Mahli Gomes back to Boston for an emotional reunion with his family.

Haiti

Rosalynn Carter, Gen. Colin Powell, Jimmy Carter, and Sen. Sam Nunn traveled to Haiti in 1994 to help avert a U.S. invasion. (Credit: The Carter Center)

In September 1994, President Carter was asked by Haiti military junta leader General Raoul Cédras to help avoid a U.S. military invasion of Haiti. The United States was calling for Cédras to reinstate the deposed leader, President Jean-Bertrand Aristide, who had been democratically elected three years earlier. President Carter relayed this information to President Clinton, who approved his undertaking a mission to Haiti with Sen. Sam Nunn (D-Ga.) and former Joint Chiefs of Staff Chairman Colin Powell.

During the negotiation, a U.S. invasion was imminent, and Powell later said he was struck by President Carter’s firmness and decisiveness, stating that the president’s actions showed toughness and a determination that impressed him. The U.S. invasion was averted, and the military junta signed an agreement to step down and restore Mr. Aristide to power.

A New York Times editorial on September 18, 1994, said: “In undertaking a special mission to Haiti for President Clinton, Jimmy Carter is showing once again that a former president can be a unique diplomatic resource. . . . Mr. Carter has not flinched from risk-taking and has played a crucial role as an honest broker, most notably in spurring nuclear talks with North Korea but also in civil conflicts in Ethiopia, the Sudan and Liberia.”

Sudan

President Carter and the Carter Center’s Conflict Resolution Program worked for more than a decade to find a peaceful resolution to Sudan's civil war. Among the program’s achievements was the negotiation of the 1995 “Guinea worm cease-fire,” which gave international health workers—including the Center’s Guinea Worm Eradication Program—an unprecedented period of almost six months of relative peace, allowing health workers to enter areas of Sudan previously inaccessible due to fighting. This was the longest humanitarian cease-fire ever achieved anywhere in the world.

In 1999, an important breakthrough for peace occurred when President Carter brokered the Nairobi Agreement between Sudan and Uganda, in which the governments pledged to stop supporting rebels acting against each other and agreed to eventually re-establish diplomatic relations.

Cuba

Former U.S. President Jimmy Carter addresses an audience in Havana, Cuba, on May 12, 2002, during a historic visit to urge the United States and Cuban governments to mend relations. Also pictured are Cuba President Fidel Castro and Rosalynn Carter. (Credit: The Carter Center)

In May 2002, President Carter became the first former or sitting U.S. president to travel to Cuba since 1928. In an unprecedented live speech broadcast on Cuban radio and television, President Carter, speaking in Spanish, called on the United States to end an “ineffective 43-year-old economic embargo” and on President Castro to hold free elections, improve human rights, and allow greater civil liberties.

“Analysts said it was the first time in 43 years that citizens had heard any public criticism of the Cuban government, much less direct condemnation of human rights violations,” President Carter wrote in his report from the trip. “I anticipated President Castro would be upset, but he greeted me after the session.”

Middle East

President Carter decided that the inaugural project of The Carter Center would be to analyze and pursue the opportunities for peace in the Middle East. In the spring of 1983, he traveled to Egypt, Israel, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, Syria, Lebanon, and Morocco, meeting with leaders and scholars. Many of them subsequently came to Emory University for a major consultation co-chaired by Presidents Ford and Carter. A book followed, The Blood of Abraham: Insights into the Middle East, laying out what remained to be done in order to achieve peace with security and justice between Israel and its neighbors.

For the next three decades, President Carter and The Carter Center continued to work, sometimes publicly and sometimes privately, to support the peace process. This seemed to be going well when the Oslo Agreement was achieved in 1993. Israel and the Palestine Liberation Organization agreed on a process that could lead to Palestinian self-government. The Carter Center assisted with the implementation of the agreement by monitoring the first election of the Palestinian National Authority in 1996. But after 2000, when Israeli-Palestinian negotiations broke down at Camp David, the peace process stalled and Israel increased the building of settlements within the West Bank and began building a separation barrier.

Frustrated by the continuing lack of progress, President Carter decided that the only way to get people moving was to be provocative. In November 2006, he published Palestine Peace Not Apartheid. The use of the word "apartheid" in the title stirred great controversy. As he explained the next year in an afterword to a new edition of The Blood of Abraham, "I was accused falsely by some as being anti-Israel. I had left the presidency thirty years before believing that Israel would soon realize its dream of peace with its neighbors. I envisioned a small nation, no longer beleaguered, exemplifying the finest ideals based on the Hebrew scriptures ... Unfortunately, I have been bitterly disappointed by the actual current state of affairs in Israel and Palestine." While disappointed, President Carter never gave up on his mission to advance peace. He continued to do everything he could for the cause: lobbying government offices, speaking out to the media, advising participants, and writing op-eds and books.

In 2009, he published We Can Have Peace in the Holy Land: A Plan That Will Work. He tried to convince Hamas and the PLO to unite with a practical Palestinian peace proposal. He tried to convince Israelis that it was both just and in their long-term interest to agree to negotiate permanent boundaries, to withdraw from occupied territories, and support the creation of a Palestinian state. While many in Israel agreed with him, recent Israeli governments have not, and he received much criticism for his efforts. Until the end, he believed that the majority of Israelis and Palestinians wanted what he wanted.

Election Observation

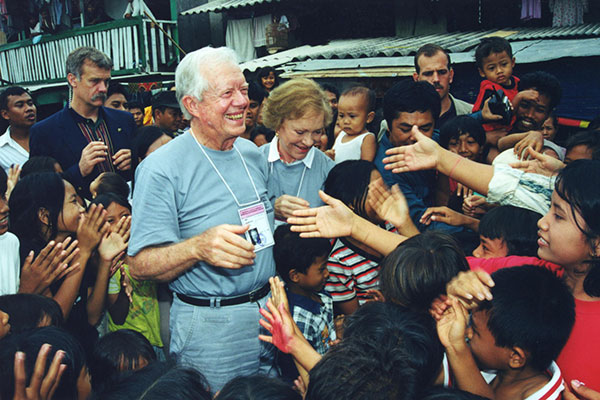

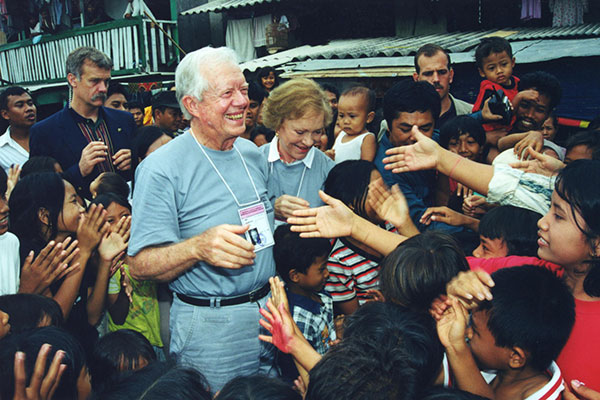

Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter in Jakarta during the Carter Center’s observation of elections in Indonesia, June 7, 1999. (Credit: The Carter Center)

Under President Carter’s leadership, The Carter Center became a pioneer in the field of election observation, helping to strengthen democracy by serving as an independent, neutral monitor in more than 110 elections in 40 countries throughout the Americas, Africa, and Asia. Before and after elections, the Center works to encourage respect for rule of law and human rights, government decisions that are open and transparent, and adequate resources for all candidates to compete fairly for public office.

Panama

Jimmy Carter briefs the media during the 1989 elections in Panama, the first observed by The Carter Center. (Credit: The Carter Center)

The Carter Center’s first election observation was in Panama in 1989. The mission was co-led by President Carter, President Ford, and former Belize Prime Minister George Price. Panama’s military dictator, Manuel Noriega, was confident of victory, but when it became clear that his candidates had lost badly, he had the results falsified. President Carter publicly denounced this to the election officials, saying in Spanish, “Son ustedes honestos, o ladrones?” (“Are you honest people, or thieves?”) After the world media reported this, Noriega’s candidates never took office, and eventually he was ousted by U.S. troops.

Nicaragua

In 1990, President Carter again was a voice for democracy in the Americas when he persuaded leftist Sandinista leader Daniel Ortega to concede the election he had lost.

“I went to see him,” President Carter recalled in The Carter Center at 30. “There were nine Sandinista comandantes (cabinet members) in the room. I met with them and told them in no uncertain terms that they had lost. They were in a quandary about how to accept it. I told them that I also had lost when I ran for re-election. I never wanted to go back into politics; but I told them that if they accepted the defeat graciously, they had a chance to run again in the future.” Indeed, after several unsuccessful runs for re-election, Ortega was elected Nicaragua’s president again in November 2006, during the fourth national Nicaraguan election observed by The Carter Center.

Human Rights

Human rights was a constant theme throughout both the Carter presidency and post-presidency and became emblematic of Jimmy Carter. His advancement of human rights throughout the world and his campaigns for the release of political prisoners in virtually every country he visited were credited with the release of thousands of such prisoners in the decades that followed his time in elective office.

With The Carter Center as their vehicle, President and Mrs. Carter spent the decades after leaving the White House attacking a host of seemingly insoluble problems throughout the world: alleviating unnecessary suffering from preventable diseases, mediating political conflicts, and building stronger democracies that protect human rights.

The Carters and The Carter Center placed a major emphasis on advancing the rights of women and girls.

In his book, A Call to Action, President Carter wrote, "The world’s discrimination and violence against women and girls is the most serious, pervasive, and ignored violation of basic human rights." In public addresses, he decried misinterpretation of religious scriptures relegating women to a secondary position compared to men and practices of genital mutilation of women, honor killings, and sex trafficking.

Carter Center programs emerged to promote women’s leadership in peacebuilding, combat sexual exploitation, strengthen the capacity of civil society organizations in less developed nations to promote gender equality, improve women's access to public information, and align religious life with human rights, especially for women and girls.

Habitat for Humanity

Beginning in 1984, Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter volunteered one week a year to build homes for Habitat for Humanity. (Credit: Habitat for Humanity)

For more than three decades, President and Mrs. Carter led annual week-long Carter Work Projects for Habitat for Humanity, a nonprofit organization that helps needy people in the United States and other countries renovate and build homes for themselves. The Carters were tireless advocates, active fundraisers, and hands-on construction volunteers. They rallied thousands of volunteers and celebrities, helping Habitat for Humanity become internationally recognized for its work. As of 2018, President and Mrs. Carter had worked alongside more than 103,000 volunteers to help build, repair, or renovate 4,331 homes.

In 1984, the international headquarters of Habitat was located in Americus, Georgia, nine miles from Plains. President Carter invited Millard Fuller, Habitat's founder, to tell him and Mrs. Carter about the organization. The Carters quickly realized that the mission aligned with their values of social justice and basic human rights. Later that year, the Carters led a busload of Georgians to New York City to work alongside 19 families, renovating an abandoned apartment building to provide the families safe, affordable housing. This was the inaugural Carter Work Project and, since then, work projects have taken place every year in a different location all over the world.

“Habitat has successfully removed the stigma of charity by substituting it with a sense of partnership,” President Carter said.

Religion

Jimmy Carter teaches Sunday School at Maranatha Baptist Church in Plains, Georgia. (Credit: The Carter Center)

President Carter described himself as a “born-again Christian.” It was clear to all who knew him that his faith was central to who he was and all that he did. Throughout his life he was active in church work, and for decades in his post-presidency he taught Sunday school at the Maranatha Baptist Church in Plains. Consistent with the earliest traditions of Southern Baptists, he was a committed defender of the separation of church and state.

In October 2000, after much soul searching, he broke with the Southern Baptist Convention over what he considered to be its increasingly rigid theological positions inconsistent with his own faith and the conscience of many of his fellow Baptists. “This has been a very difficult thing for me,” Carter told The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. “My grandfather, my father, and I have always been Southern Baptists, and for 21 years, since the first political division took place in the Southern Baptist Convention, I have maintained that relationship. I feel I can no longer in good conscience do that.” He said that after years of feeling “increasingly uncomfortable and somewhat excluded,” he and Mrs. Carter had reached the decision to disassociate themselves from the Southern Baptist Convention. The final determination was made, he said, with the passage of a denominational statement that prohibited women from being pastors, said wives should be submissive to their husbands, and eliminated language from an earlier version that said “the criterion by which the Bible is to be interpreted is Jesus Christ.”

President Carter repeatedly sought to find common ground and foster unity among Baptists and other Christian groups. In concert with former President Clinton, he led an effort that convened more than 14,000 people at an early 2008 “Celebration of a New Baptist Covenant” meeting in Atlanta. The three-day gathering united major Black and white Baptist groups, and President Carter said he hoped the gathering would help convince conservative Southern Baptists and other Christians to end divisions over the Bible and politics. “We can disagree on the death penalty, we can disagree on homosexuality, we can disagree on the status of women and still bind our hearts together in a common, united, generous, friendly, loving commitment,” he told the assembly.

Author

President Carter wrote 32 books. Some of his books are now in revised editions, and include: Why Not the Best?, 1975, 1996; A Government as Good as Its People, 1977, 1996; Keeping Faith: Memoirs of a President, 1982, 1995; Negotiation: The Alternative to Hostility, 1984, 2003; The Blood of Abraham: Insights into the Middle East, 1985, 1993, 2007; Everything to Gain: Making the Most of the Rest of Your Life, written with Rosalynn Carter, 1987, 1995; An Outdoor Journal: Adventures and Reflections, 1988, 1994; Turning Point: A Candidate, a State, and a Nation Come of Age, 1992; Talking Peace: A Vision for the Next Generation, 1993, 1995; Always a Reckoning, and Other Poems, 1995; The Little Baby Snoogle-Fleejer, illustrated by Amy Carter, 1995; Living Faith, 1996; Sources of Strength: Meditations on Scripture for a Living Faith, 1997; The Virtues of Aging, 1998; An Hour before Daylight: Memories of a Rural Boyhood, 2001; Christmas in Plains: Memories, 2001; The Nobel Peace Prize Lecture, 2002; The Hornet’s Nest: A Novel of the Revolutionary War, 2003; Sharing Good Times, 2004; Our Endangered Values: America’s Moral Crisis, 2005; Palestine Peace Not Apartheid, 2006, 2007; Beyond the White House: Waging Peace, Fighting Disease, Building Hope, 2007; A Remarkable Mother, 2008; We Can Have Peace in the Holy Land: A Plan That Will Work, 2009; The White House Diary, 2010; Through the Year with Jimmy Carter: 366 Daily Meditations from the 39th President, 2011; as general editor, NIV Lessons from Life Bible: Personal Reflections with Jimmy Carter, 2012; A Call to Action: Women, Religion, Violence, and Power, 2014; The Paintings of Jimmy Carter, 2014; A Full Life: Reflections at Ninety, 2015; The Craftsmanship of Jimmy Carter, 2018; and Faith: A Journey for All, 2018.

Hornet’s Nest was the first novel ever written by a president, and its cover is evidence of President Carter’s wide range of talents: dissatisfied with the artwork his publisher proposed for the book, Jimmy Carter painted his own to adorn the dust jacket. He garnered Grammy Awards for three of his audio books, winning for Best Spoken Word Album in 2018 (Faith: A Journey for All), 2015 (A Full Life: Reflections at Ninety), and 2006 (Our Endangered Values: America’s Moral Crisis). He was nominated and a finalist for six additional Grammy Awards.

President Ford

In a development that would hardly have been predicted by either of them when presidential candidate Carter bested President Gerald R. Ford in the 1976 election, the two former presidents became close friends. They ignored any continuing political differences and concentrated on areas of agreement, working together on dozens of projects and co-chairing several national commissions. These members of that most exclusive of clubs, former presidents of the United States, developed a relationship of friendship and mutual respect that was important to both men.

At the January 3, 2007, funeral service for President Ford, President Carter eulogized his predecessor: “You learn a lot about a man when you run against him for president, and when you stand in his shoes and assume the responsibilities that he has borne so well, and perhaps even more after you both lay down the burdens of higher office and work together in a nonpartisan spirit of patriotism and service.” President Carter spoke of the two men’s “valued personal friendship” and “personal bond,” adding, “We enjoyed each other’s private company. And he and I commented often that, when we were traveling somewhere in an automobile or airplane, we hated to reach our destination, because we enjoyed the private times that we had together.”

Alluding to the opening line of his 1977 inaugural speech, President Carter, choking back emotion, concluded his remarks: “I still don’t know any better way to express it than the words I used almost exactly 30 years ago: ‘For myself and for our nation, I want to thank my predecessor for all he did to heal our land.’”

United States Federal Election Reform

After the failures of the electoral system in Florida during the 2000 presidential election, the need for comprehensive reform became very clear. President Carter and President Ford agreed to co-chair a bipartisan commission to study and address the problems. The national commission, organized by The Miller Center of the University of Virginia, received support on the federal, state, and local levels. Its recommendations were submitted to the president and Congress and led to the Help America Vote Act of 2002. A follow-up commission, launched in 2005 with President Carter and former Secretary of State James Baker as co-chairs, proposed additional reforms, some of which inspired state legislation.

The Elders

President Carter was one of nine founding members of a group of independent global leaders brought together in 2007 by Nelson Mandela. While no longer holding office, they remained committed to peace and human rights. They worked to bring attention to serious problems in nations such as Syria, Zimbabwe, and Myanmar, as well as advocating for equality for girls and women and the need to address climate change.

Emory University

As University Distinguished Professor since 1982, President Carter taught and lectured in a variety of classes, conferences, and special forums for students, faculty, and staff in all the schools and colleges. His annual Town Hall Meeting became one of Emory’s most important traditions and a rite of passage for freshmen. At The Carter Center, President Carter worked closely with Emory associates, especially with Emory presidents, but also with trustees, faculty, and student interns.

Presidential Medal of Freedom

In 1999, President Clinton awarded America’s highest civilian honor, the Presidential Medal of Freedom, to both President and Mrs. Carter. President Clinton said the Carters had formed an “extraordinary partnership,” and that “Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter have done more good for more people in more places than any other couple on the face of the Earth.”

Nobel Peace Prize

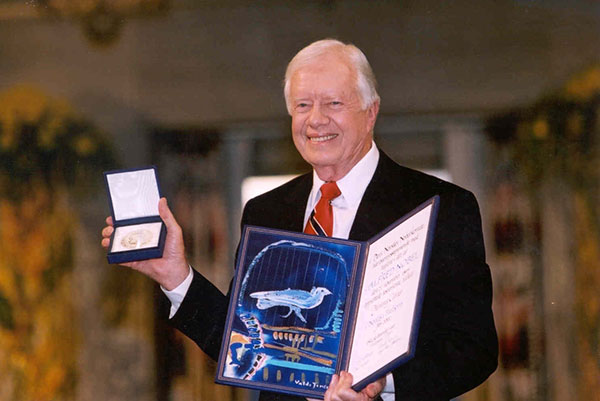

In 2002, Jimmy Carter was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize “for his decades of untiring effort to find peaceful solutions to international conflicts, to advance democracy and human rights, and to promote economic and social development.” (Credit: The Carter Center)

A key moment in his post-presidency occurred on December 10, 2002, when the Norwegian Nobel Committee presented President Carter the Nobel Peace Prize. The committee noted President Carter’s role in negotiating the Camp David Accords during his presidency as well as his post-presidential work at The Carter Center: “Through his Carter Center, which celebrates its 20th anniversary in 2002, Carter has since his presidency undertaken very extensive and persevering conflict resolution on several continents. He has shown outstanding commitment to human rights, and has served as an observer at countless elections all over the world. He has worked hard on many fronts to fight tropical diseases and to bring about growth and progress in developing countries. Carter has thus been active in several of the problem areas that have figured prominently in the over one hundred years of Peace Prize history.”

In his wide-ranging acceptance speech in Oslo, he expressed his gratitude to his wife, Rosalynn, his colleagues at The Carter Center, and the “many others who continue to seek an end to violence and suffering throughout the world.”

President Carter perhaps best summed up the guiding principles of his post-presidency service when he said, “I am not here as a public official, but as a citizen of a troubled world who finds hope in a growing consensus that the generally accepted goals of society are peace, freedom, human rights, environmental quality, alleviation of suffering, and the rule of law.”

He concluded his remarks with this declaration: “War may sometimes be a necessary evil. But no matter how necessary, it is always an evil, never a good. We will not learn how to live together in peace by killing each other’s children. The bond of our common humanity is stronger than the divisiveness of our fears and prejudices. God gave us the capacity for choice. We can choose to alleviate suffering. We can choose to work together for peace. We can make these changes—and we must.”

He was the third U.S. president to be awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, joining presidents Theodore Roosevelt (1906) and Woodrow Wilson (1919). President Obama was awarded the prize in 2009.

The USS Jimmy Carter

The last of the Seawolf class of attack submarines, the most heavily armed submarine ever built, was named after the only president ever to serve on a submarine. In the February 2005 commissioning ceremony in Groton, Connecticut, President Carter said, “The most deeply appreciated and emotional honor I’ve ever had is to have this great ship bear my name.” He said he expected the crew of the USS Jimmy Carter to use the ship’s “extraordinary capabilities—many top secret—to preserve peace, to protect our country, and to keep high the banner of human rights around the world.”

Presidential Longevity

Jimmy Carter celebrates his 90th birthday at The Carter Center in Atlanta on October 1, 2014. (Credit: The Carter Center)

President Carter reached several significant milestones for longevity. On March 22, 2019, he became the longest-living president in U.S. history. On October 17, 2019, Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter established the record for the longest marriage of a presidential couple, 73 years and 102 days, passing George H.W. and Barbara Bush. When Mrs. Carter died on November 19, 2023, the Carters had been married for 77 years and 135 days.

On May 23, 2006, Jimmy Carter and Walter Mondale became the president and vice-president who had survived the longest after their term in office. They passed President John Adams and Vice President Thomas Jefferson who had left office on March 4, 1801. Both died on July 4, 1826. September 8, 2012, marked 11,554 days for Jimmy Carter as a former president, surpassing the record set by Herbert Hoover.