The Early Years

James “Jimmy” Earl Carter, Jr., was born on October 1, 1924, to James Earl and Lillian Carter. In this photograph, he is one month old in his mother’s arms. (Credit: Jimmy Carter Presidential Library)

In his 1975 autobiography, Why Not the Best?, presidential candidate Carter wrote, “Within our free society each of us has an opportunity to develop a wide range of abilities, characteristics, responsibilities, and interests. I am a Southerner and an American. I am a farmer, an engineer, a father and husband, a Christian, a politician and former governor, a planner, a businessman, a nuclear physicist, a naval officer, a canoeist, and, among other things, a lover of Bob Dylan’s songs and Dylan Thomas’s poetry.”

It was not by chance that the future president would first identify himself as a Southerner. He grew up in southwest Georgia during the Great Depression and felt deeply about his roots. His family had been in Georgia since the 1700s, and his father was the fourth generation—and Jimmy Carter was to become the fifth—to own and farm land in Sumter County near Plains, the small town where he was born on October 1, 1924, and to which he returned following his presidency.

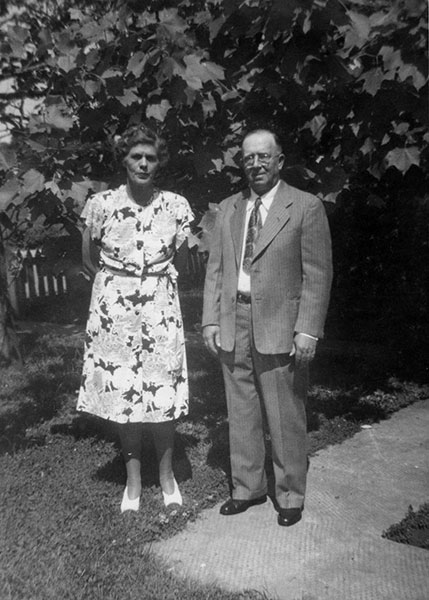

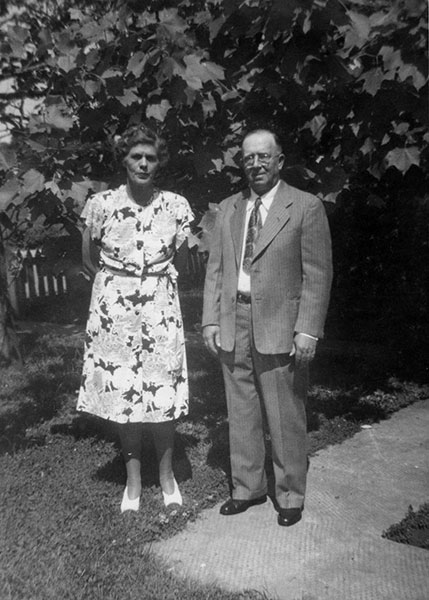

Jimmy Carter’s Parents

Parents, Lillian and James Earl Carter. (Credit: Jimmy Carter Presidential Library)

In Why Not the Best?, Jimmy Carter affectionately described his parents. His father, James Earl Carter Sr.—known as “Mr. Earl”—“was a very firm but understanding director of my life and habits. In retrospect, the farm work sounds primitive and burdensome, but at the time it was an accepted farm practice, and my dad himself was an unusually hard worker. Also, he was always my best friend.” The son said his father “was an extremely competent farmer and businessman who later developed a wide range of interest in public affairs” and “was extremely intelligent, well read about current events, and was always probing for innovative business techniques or enterprises.”

Jimmy Carter’s mother, widely known as “Miss Lillian,” was a registered nurse. “During my formative years,” he wrote, “she worked constantly, primarily on private duty either at the nearby hospital or in patients’ homes ... and during her off-duty hours she had to perform the normal functions of a mother and a housekeeper. She served as a community doctor for our neighbors and for us, and was extremely compassionate towards all those who were afflicted with any sort of illness. Although my father seldom read a book, my mother was an avid reader, and so was I.” Miss Lillian later famously joined the Peace Corps at age 68 and served for two years in India.

Life on the Farm

Although President Carter was the first U.S. president to be born in a hospital, there was no indoor plumbing or electricity on the family farm in Archery during his early years. In Why Not the Best?, he described how, when he was a teenager, “an almost unbelievable change took place in our lives when electricity came to the farm. The continuing burden of pumping water, sawing wood, building fires in the cooking stove, filling lamps with kerosene, and closing the day’s activity with the coming of night. . .all these things changed dramatically.” But his family had done well. In addition to the large family farm, Jimmy Carter’s father “bought peanuts from other farmers on a contract basis for a nearby oil mill, and . . . he eventually began to sell fertilizer, seed, and other supplies to neighboring farmers.”

Jimmy Carter remembered walking from the farm to sell boiled peanuts on the streets of Plains from the time he was a youngster: “Even at that early age of not more than six years, I was able to distinguish very clearly between the good people and the bad people of Plains. The good people, I thought, were the ones who bought boiled peanuts from me! I have spent much time since then in trying to develop my ability to judge other people, but that was the simplest method I ever knew, despite its limitations. I think about this every time I am tempted to judge other people hastily.”

Education

Naval portrait of Jimmy Carter. (Credit: Jimmy Carter Presidential Library)

Throughout his career in public service, President Carter repeatedly paid tribute to his beloved high school teacher, Miss Julia Coleman, who encouraged him to read widely, introduced a 12-year-old Jimmy Carter to War and Peace, and in the small, agriculture-based Plains community exposed all students to literature, art, music, plays, and composition. Many former students fondly recall Miss Coleman telling each of her classes, “Study hard. One of you could become the president of the United States!” Little did she know that one of her students would indeed do so, and that another would be first lady. In both his inauguration and Nobel Peace Prize speeches, the president referred to Miss Coleman’s repeated admonition: “We must adjust to changing times and still hold to unchanging principles.” It was an admonition that those who worked most closely with Jimmy Carter felt aptly characterized a life of almost constant change and unwavering commitment to high principle.

In An Hour Before Daylight, the former president recalled that from the time he was 5 years old he had decided to attend the Naval Academy and become a naval officer. He was inspired by his Uncle Tom Gordy, younger brother of his mother, who was an enlisted man in the Navy and sent him mementos and letters “filled with information about the exotic places his ships were visiting.”

President Carter, the first Carter in his line to graduate from high school, attended Georgia Southwestern College and the Georgia Institute of Technology before proceeding to the Naval Academy in 1943. After graduation, he became a submariner and won assignment to the Navy’s elite new nuclear submarine program.

Why Not the Best?

That program put him under the command and strong influence of then-Capt. Hyman Rickover, a stern taskmaster who President Carter said “had a profound effect on my life—perhaps more than anyone except my own parents.” In his presidential campaign autobiography and speeches, candidate Carter recounted repeatedly how when he interviewed for the nuclear submarine program, Rickover asked about his academic standing in his Naval Academy class. The future president responded that he was 59th out of 820, and awaited Rickover’s praise. Instead, the captain asked, “Did you do your best?” Faltering, naval officer Carter gulped and said, “No, sir, I didn’t always do my best.” Recounted President Carter: “He looked at me for a long time, and then turned his chair around to end the interview. He asked one final question, which I have never been able to forget—or to answer. He said, ‘Why not?’ I sat there for a while, shaken, and then slowly left the room.”

That question provided the future president with both the title of his campaign-related autobiographical book, Why Not the Best?, and his 1976 presidential campaign slogan. As the years passed, it was clear that those words had also become an inspiration for an extraordinary life.

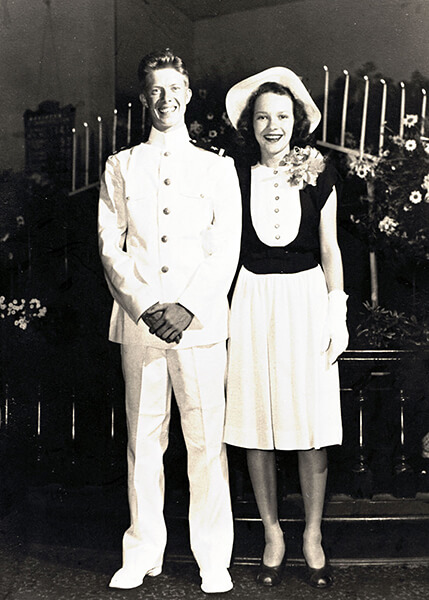

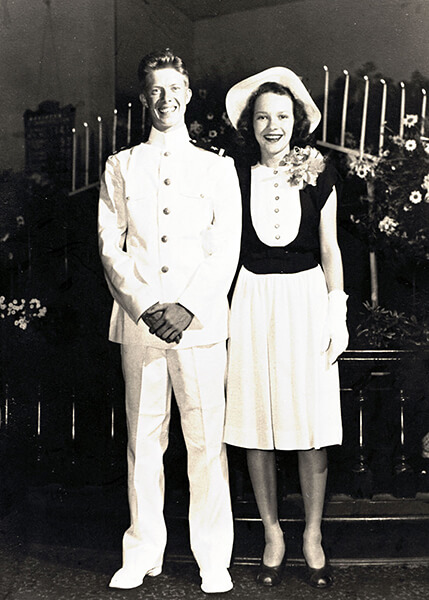

Rosalynn Smith Carter

Jimmy Carter and Rosalynn Smith were married July 7, 1946, in Plains, Georgia. (Credit: Jimmy Carter Presidential Library)

On July 7, 1946, the summer after his graduation from Annapolis, Naval officer Carter married Rosalynn Smith, who was also the fifth generation of her family to live in the Plains area. The future president wrote in Why Not the Best? that after his first date with Rosalynn, less than a year before they were married, he “returned home later that night and told my mother that Rosalynn had gone to the movies with me. Mother asked if I liked her, and I was already sure of my answer when I replied, 'She’s the girl I want to marry.'" Jimmy Carter referred frequently to his "full partner" or "equal partner" Rosalynn, and their work together to aid the world as projects "we did,” rather than "I did." In Keeping Faith: Memoirs of a President, he wrote: "We had been ridiculed at times for allowing our love to be apparent to others. It was not an affectation, but was as natural as breathing." On the day she passed away, President Carter said in a statement, "Rosalynn was my equal partner in everything I ever accomplished. She gave me wise guidance and encouragement when I needed it. As long as Rosalynn was in the world, I always knew somebody loved and supported me."

The Navy and the Return to Plains

Jimmy Carter returned to Plains to run the family business. (Credit: Jimmy Carter Presidential Library)

In his campaign autobiography, President Carter described his love of the Navy. He and his growing family enjoyed their assignments in Hawaii, California, Virginia, and Connecticut, and a sense of seeing more of the world. But his father’s 1953 death from cancer and the realization of the positive role his father had played in the life of the community led him to resign his commission that same year and take over the family farm and business.

Although the first-year business profit was less than $200, with the help of his wife he eventually expanded the business into a flourishing enterprise. Besides farming 3,100 acres, the family had a seed and fertilizer business, warehouses, a peanut shelling plant, a cotton gin, and a farm supply operation.

Matter of Principle

It was during the fledgling days of his business life that Jimmy Carter faced an early test of principle. It was the 1950s in the Deep South, and segregation advocates formed White Citizens’ Councils throughout the region. The groups were determined to maintain school segregation, and Jimmy Carter was soon visited by two council members trying to sign him up—the chief of police and the local railroad depot agent. He declined. A few days later the two paid another visit, claiming that virtually every adult white male in the community had joined the council except him. He again declined.

After a further few days, the two returned with several close friends of his, some of them customers of his seed and fertilizer business. They told him his refusal to join would injure his reputation and harm his business, and that out of concern for his welfare they would pay his council dues for him. He wrote in Why Not the Best?: “My response was that I had no intention of joining the organization on any basis; that I was willing to leave Plains if necessary; that the $5 dues requirement was not an important factor; and that I would never change my mind. Rosalynn and I became quite troubled about our future.” A small boycott organized against him proved to be short-lived. But Jimmy Carter’s stand on principle would become only one of many.

Politics Beckons—State Senator and Governor

This poster is from Jimmy Carter’s Georgia State Senate campaign. He was elected to the Georgia State Senate twice, in 1962 and 1964. (Credit: Jimmy Carter Presidential Library)

As his businesses prospered, the future president grew more active in civic affairs. He became a member of both the county library board and hospital authority, was elected county school board chairman, became the first president of the Georgia Planning Association, state president of the Certified Seed Organization, and district governor of Lions Clubs International. He ran for the state Senate in 1962. He appeared to have lost the Democratic primary after a county political “boss” stuffed a ballot box, but Jimmy Carter and his friends worked to expose the fraud and through various legal proceedings got the results overturned. He went on to win the general election.

Although he had low statewide name recognition, he ran for governor in 1966. He finished third in the Democratic primary. He waited about a month, then launched another campaign for governor.

He made 1,800 speeches in the next four years. He wrote in Why Not the Best?, “Rosalynn and I in that time personally shook hands with more than 600,000 people in Georgia—more than half the total number who vote. During the last few months each of us would meet at least three factory shifts each day.” The energy and tenacity he showed in this campaign served as a model for his presidential race.

Jimmy Carter became Georgia’s 76th governor on January 12, 1971. (Credit: Jimmy Carter Presidential Library)

After an upset victory in the Democratic primary, Jimmy Carter easily won election as governor, and in his inaugural address declared, “At the end of this long campaign, I believe I know the people of this state as well as anyone. Based on this knowledge of Georgians north and south, rural and urban, liberal and conservative, I say to you quite frankly that the time for racial discrimination is over. Our people have already made this major and difficult decision, but we cannot underestimate the challenge of hundreds of minor decisions yet to be made. Our inherent human charity and our religious beliefs will be taxed to the limit. No poor, rural, weak, or Black person should ever have to bear the additional burden of being deprived of the opportunity for an education, a job, or simple justice.”

The speech gained widespread attention and, along with other actions, led to stories about Carter as a “New South” governor. This included his first of nearly 30 appearances on the cover of Time magazine. The cover story of May 31, 1971, was titled “Dixie Whistles a Different Tune” and subtitled “Georgia’s Governor Jimmy Carter.” Later in his term in office, Governor Carter in 1974 arranged for the hanging of a portrait of Martin Luther King Jr. in the state Capitol – an act that had great symbolism in the context of the times.

As governor, he hired the first African American to serve on the staff of a Georgia governor, and increased employment of African Americans in state government by nearly 40 percent. This included hiring the first African Americans in positions of responsibility in many state government agencies. He appointed the first African Americans to serve on the Board of Regents of the University System of Georgia, the state Board of Pardons and Paroles, and as a trial court judge.

For the first time, an African American state trooper was assigned as a member of a Georgia governor’s security detail. When Jimmy Carter became governor, only three African Americans were members of major state boards and commissions. There were 53 when he left office.

His service as governor of Georgia from 1971-1975 and Georgia state senator from 1963-1967 was marked by the same determination to engage difficult and controversial issues as evidenced in his presidency, ranging from bureaucracy and budgeting to prison reform, education, and the environment.

As a state senator, he was responsible for Georgia’s first program to equalize funding for education between wealthy and poor school systems. As governor, he followed up on that initiative with an educational reform package that reduced class size, supported vocational education, increased the state’s commitment to preschool education, and laid the groundwork for the eventual adoption of a statewide kindergarten program.

Other accomplishments included a drastic reorganization of state government that streamlined hundreds of state agencies, boards, bureaus, and commissions into dozens of more efficient, more accountable state agencies; reform of the state’s budgeting process; prison reform; professionalizing investment of state funds; reform of the state’s criminal justice system, including introduction of a merit system for selection of judges; and initiation of significant new mental health programs. Governor Carter appointed more women and minorities to his staff, the judiciary, and major state boards and agencies than all of his predecessors combined, and he became the first governor in the country to veto a Corps of Engineers water project because of environmental concerns and cost inefficiencies.

Halfway through his term as governor he began planning his run for the presidency. It was a campaign that carried him from relative obscurity to the White House and a prominent platform on the international stage—a platform he used to help better the world for decades beyond his four years in office.